The parsing stage involves 4 principal stages:

- Preprocessing

- Runs the C preprocessor, handling

#directives

- Runs the C preprocessor, handling

- Lexing

- Tokenises the output of the preprocessor

- Parsing

- Builds a highly generic AST which can parse a much larger set of programs than are legal in C

- This allows emitting significantly clearer diagnostics than if it parsed more strictly

- Typing

- Types the tree and performs most validation to reject invalid programs

Lexer

Being able to perform all of these steps very quickly is essential, and so these components have been carefully optimised. The current parser-lexer-preprocessor combination can achieve approximately 600k lines-of-code per second per thread, a very similar rate to clang and marginally faster than gcc. These benchmarks were performed on generated code from csmith, JCC itself, and the sqlite3 amalgamation file.

Preprocessing will mostly be ignored here, but it is important to understand how it interacts with the lexer and the parser. The preprocessor produces struct preproc_tokens in a forward-only manner - it cannot backtrack. Each preprocessor token is 1-1 with a lexer token, no splitting nor merging occurs by the lexer.

The driver invokes the parser, which creates lexer and preprocessor instances. As parsing occurs, it interacts with the lexer via a few methods:

struct lex_pos lex_get_position(struct lexer *lexer);

struct text_pos lex_get_last_text_pos(const struct lexer *lexer);

void lex_peek_token(struct lexer *lexer, struct lex_token *token);

void lex_consume_token(struct lexer *lexer, struct lex_token token);

void lex_backtrack(struct lexer *lexer, struct lex_pos position);lex_get_position and lex_get_last_text_pos

These are used to query the current position of the lexer. lex_get_position returns an opaque type struct lex_pos which represents the internal lexer position and can be used for backtracking via lex_backtrack, whereas lex_get_last_text_pos is used to retrieve a struct text_pos which is used for both diagnostic generation and giving each AST node a text span indicating its position in the source.

lex_peek_token and lex_consume_token

lex_peek_token will return the next token in the stream of lex tokens, so the parser can determine if it wants to consume it. If it does, it will then call lex_consume_token with that token to move the lexer forward to the next token.

lex_backtrack

This moves the lexer's internal position back to the position represented by struct lex_pos. The lexer does not re-lex tokens (as this would be wasteful), and instead maintains an internal buffer of pre-lexed tokens which it reads from when possible, only lexing a new token if none are left in the buffer.

Lexing process

When there are no tokens left in its buffer, the lexer will lex a new token. The first step is to retrieve the next token from the preprocessor:

struct preproc_token preproc_token;

do {

preproc_next_token(lexer->preproc, &preproc_token,

PREPROC_EXPAND_TOKEN_FLAG_NONE);

} while (preproc_token.ty != PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_EOF &&

!text_span_len(&preproc_token.span));Note: The preprocessor token flags are irrelevant as they are only used by the preprocessor during macro expansion

The preprocessor may generate empty tokens (such as from macro-references of empty definitions) and the lexer skips these. Other token types are skipped later, but it is important to do this here because the preprocessor may generate empty tokens of any type (this allows it to perform certain operations more efficiently), and so a token of type PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_IDENTIFIER that is empty cannot be handed to the parser.

Because the preprocessor must be aware of various different token types (punctuators, preproc-numbers, identifiers, etc) the work of the lexer is relatively limited.

The identifier type of token maps to a lex token of either identifier or keyword. The refine_ty method performs a hashtable lookup against a pre-built keyword table, returning the relevant keyword type or identifier if it is not a keyword. Similarly, because the preprocessor relies on punctuation for much of its syntax, these tokens can simply be mapped from the preprocessor type to the lexer type via preproc_punctuator_to_lex_token_ty, which is simply a large switch table (that is optimised into a LUT by clang).

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_IDENTIFIER: {

enum lex_token_ty ty = refine_ty(&preproc_token);

*token = (struct lex_token){

.ty = ty, .text = preproc_token.text, .span = preproc_token.span};

return;

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_PUNCTUATOR:

*token = (struct lex_token){

.ty = preproc_punctuator_to_lex_token_ty(preproc_token.punctuator.ty),

.text = preproc_token.text,

.span = preproc_token.span};

return;

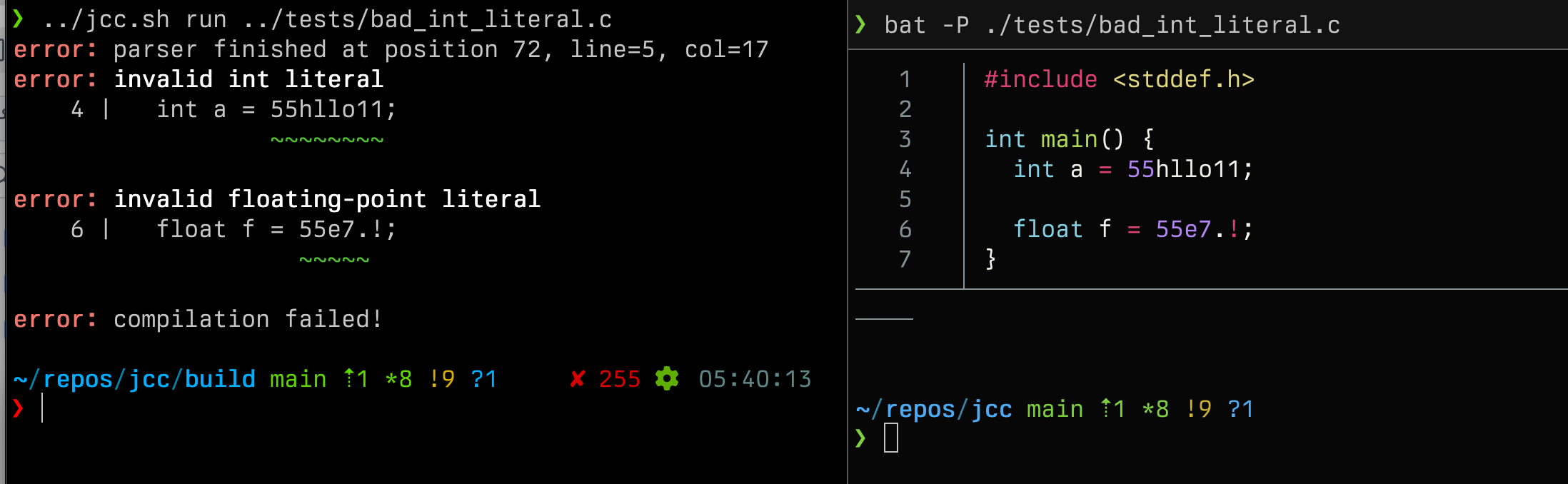

}The preprocessor number token type covers all integer and float literals, as well as various illegal number-like literals. lex_number_literal does not truely parse the number, but uses the suffixes (such as 55UL or 33.7f) to determine the type of the literal as this is encoded within the token. It intentionally allows illegal literals so the parser can reject them with a diagnostic.

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_PREPROC_NUMBER:

*token = (struct lex_token){.ty = lex_number_literal(&preproc_token),

.text = preproc_token.text,

.span = preproc_token.span};

return;The final category is string literals, which also includes character literals - the naming is for symmetry with standard preprocessor parlance.

It simply determines the type of string or character (wide or regular) and returns the token.

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_STRING_LITERAL:

*token = (struct lex_token){.ty = lex_string_literal(&preproc_token),

.text = preproc_token.text,

.span = preproc_token.span};

return;EOF & Unknown type tokens are passed to the parser so it can end (on EOF) or emit a diagnostic (on unknown token);

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_UNKNOWN:

*token = (struct lex_token){.ty = LEX_TOKEN_TY_UNKNOWN,

.text = preproc_token.text,

.span = preproc_token.span};

return;

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_EOF:

*token = (struct lex_token){.ty = LEX_TOKEN_TY_EOF,

.text = preproc_token.text,

.span = preproc_token.span};

return;Other token types are skipped or not relevant

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_COMMENT:

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_NEWLINE:

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_WHITESPACE:

continue;

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_DIRECTIVE:

BUG("directive token reached lexer");

case PREPROC_TOKEN_TY_OTHER:

TODO("handler OTHER preproc tokens in lexer");

}Parser

The parser is a hand-written recursive-descent parser. It builds a very flexible AST with significantly weaker rules than C in order to faciliate good diagnostic generation as well as making error-recovery significantly easier.

struct var_table

The var-table type is used by typechecking to manage types and variables across different scopes. It supports pushing and popping scopes, and namespacing of different types (such that struct foo and union foo do not conflict). We re-use this type within the parser to deal with the typedef ambiguity problem. The parser maintains a single var table, called ty_table. When it parses a declaration, it notes whether typedef was present, and if so it adds the names from the declaration into this table. It does not record the types involved, as that information is not yet available and is unnecessary here.

Then, the parse_typedef_name function uses this table to determine if the name in question is a typedef name:

static bool parse_typedef_name(struct parser *parser,

struct lex_token *typedef_name) {

struct lex_token identifier;

lex_peek_token(parser->lexer, &identifier);

if (identifier.ty != LEX_TOKEN_TY_IDENTIFIER) {

return false;

}

// retrieves the string from the identifier

struct sized_str name = identifier_str(parser, &identifier);

// VAR_TABLE_NS_TYPEDEF is the namespace

// As we only use it for typedefs, it is not needed in parser (only typechk) but we keep it for consistency

struct var_table_entry *entry =

vt_get_entry(&parser->ty_table, VAR_TABLE_NS_TYPEDEF, name);

if (!entry) {

return false;

}

*typedef_name = identifier;

lex_consume_token(parser->lexer, identifier);

typedef_name->span = identifier.span;

return true;

}In general, the aim of the parser's grammar is to be as flexible as possible while still allowing sensible error recovery. For example, it allows all forms of type specifiers anywhere (such as inline int a or register int main();), as this does not make recovery any harder but can easily be rejected in the typecheck pass. The parser will emits its own diagnostics in scenarios where it knows which token is required next (such as missing close-brackets or semicolons), but in all these scenarios it is able to return an error expression (AST_EXPR_TY_INVALID) and continue parsing. The error diagnostics will then cause termination after parsing has completed.

Expression parsing

Precedence climbing is used for parsing binary expressions. Unary operators are parsed as part of the grammar in classic recursive descent style, with common prefixes lifted from their nodes for efficiency. For example, the core of the top-level expression parser:

// All paths require an atom_3, so we lift the common prefix

struct ast_expr atom;

if (!parse_atom_3(parser, &atom)) {

return false;

}

// Explicitly pass the atom_3 to parse_assg

struct ast_assg assg;

if (parse_assg(parser, &atom, &assg)) {

expr->ty = AST_EXPR_TY_ASSG;

expr->assg = assg;

expr->span = MK_TEXT_SPAN(start, lex_get_last_text_pos(parser->lexer));

return true;

}

// all non-assignment expressions

// This function is the entrypoint to the precedence climber

struct ast_expr cond;

if (!parse_expr_precedence_aware(parser, 0, &atom, &cond)) {

lex_backtrack(parser->lexer, pos);

return false;

}

// A ternary is the lowest precedence other than comma operator

// So we have now found its prefix (an expr), we attempt to parse the rest of it

if (!parse_ternary(parser, &cond, expr)) {

*expr = cond;

}Because in macro-heavy code, ternary and compound expressions are extremely common, minimising backtracking is essential. During the first iteration of bootstrapping the compiler, parsing the rv32i/emitter.c file would take ~4s and the x64/emitter.c file would stack overflow (both of these use macros extensively for encoding instructions). By lifting these prefixes, the parse time of both was reduced to under 50ms.

Rewriting this code to use full Pratt parsing for unary and binary expressions is on my TODO list as I suspect it will improve performance and be clearer code.

Debugging

As with all sections of the compilers, parsing has a general purpose prettyprint tool that prints the AST. For example, the AST for a simple hello-world program:

PRINTING AST

DECLARATION

DECLARATION SPECIFIER LIST

DECLARATION SPECIFIER

TYPE SPECIFIER

INT

INIT DECLARATOR LIST

DECLARATOR

DIRECT DECLARATOR LIST

DIRECT DECLARATOR

IDENTIFIER 'printf'

DIRECT DECLARATOR

FUNC DECLARATOR

PARAM

DECLARATION SPECIFIER LIST

DECLARATION SPECIFIER

CONST

DECLARATION SPECIFIER

TYPE SPECIFIER

CHAR

ABSTRACT DECLARATOR

POINTER LIST

POINTER

DECLARATION SPECIFIER LIST

DIRECT ABSTRACT DECLARATOR LIST

PARAM

VARIADIC

ATTRIBUTE LIST

FUNCTION DEFINITION

COMPOUND STATEMENT:

EXPRESSION

COMPOUND EXPRESSION:

EXPRESSION

CALL

EXPRESSION

VARIABLE 'printf'

ARGLIST:

EXPRESSION

CONSTANT "Hello, World!\n"

RETURN

EXPRESSION

CONSTANT 0